This past July, I had the honor of being selected as one of 79 “38th Voyagers” to sail on the restored whaling ship Charles W. Morgan, as she made her way along the New England coast. The program, through Mystic Seaport in Connecticut, and partly funded by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, sought to bring artists, scientists, writers, and other academics on board, to see what their experiences would create.

I was placed in the Provincetown to Boston leg, and what follows is my own experience on the ship:

Part Two

“Real strength never impairs beauty or harmony, but it often bestows it, and in everything imposingly beautiful, strength has much to do with magic.” Herman Melville

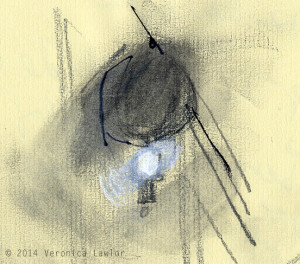

As we slept on the Charles W. Morgan, we were protected by a beacon of light. Hanging above the bowsprit of the ship, this nightlight was a sentinel, letting all other ships know that we were moored for the night.

The morning of our sail, I awoke suddenly in my bunk, wondering why I was rocking. Then I remembered, I had spent the night sleeping on a ship, safeguarded by a night light. I lay there for a moment, wondering if it was time to get up, when one of the crew came into the fo’c’sle and said gently, “OK voyagers, this is your 5:15 wake up call. It’s a little wet out there, so put on some layers.”

I maneuvered myself out of the tight quarters, scurried over to the littlest sink I’ve ever seen to brush my teeth, decided makeup was superfluous, and put a sweatshirt on under my official Voyager t-shirt. I hope I brushed my hair, but can’t be sure I did in my haste to get on deck.

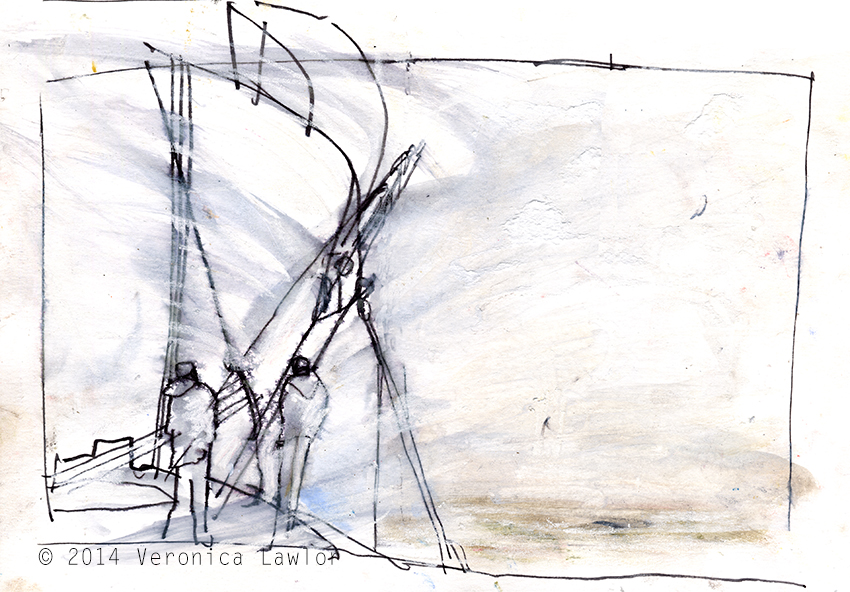

I climbed the ladder up to the deck, thinking of coffee and maybe a roll or pastry, like this was some pleasure cruise. Instead, I was greeted by this sight:

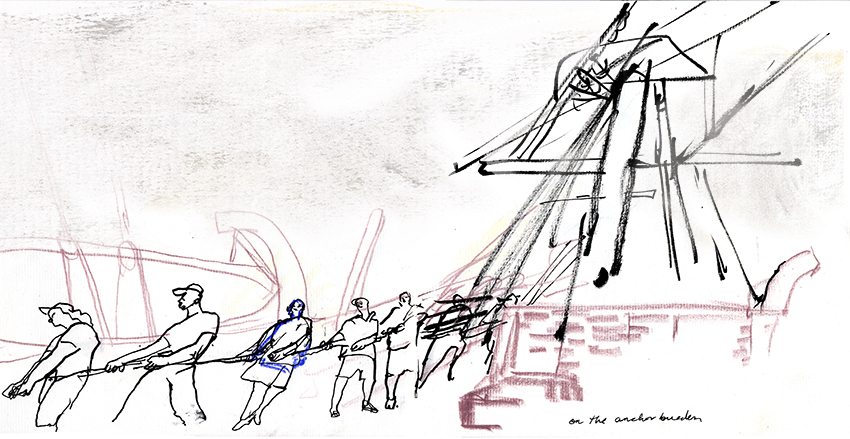

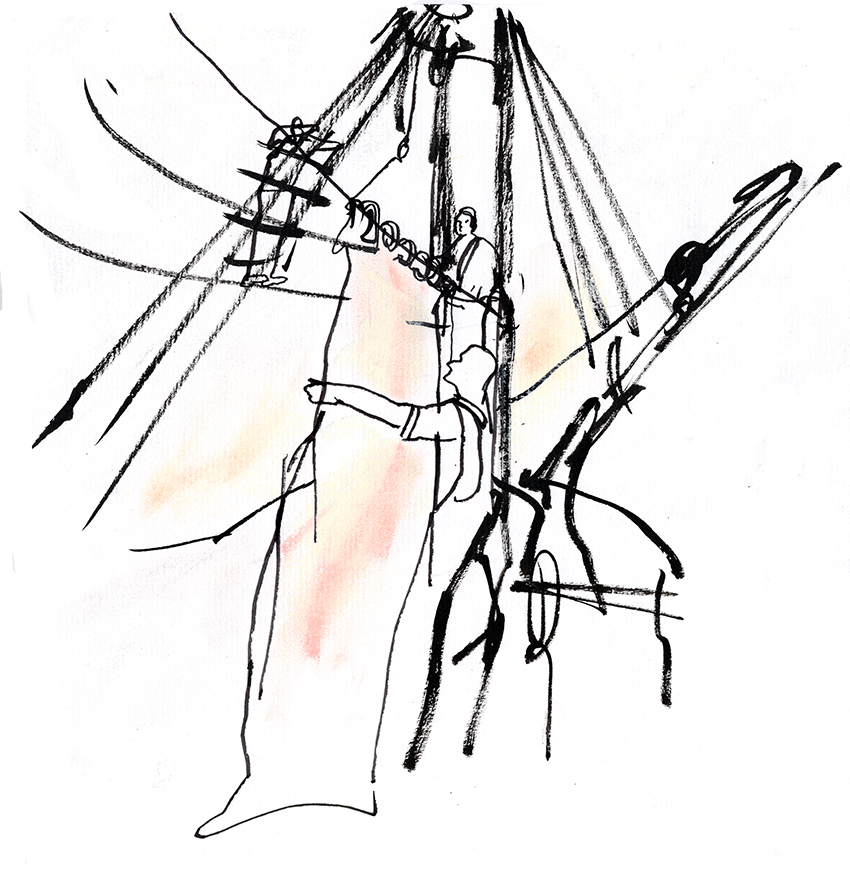

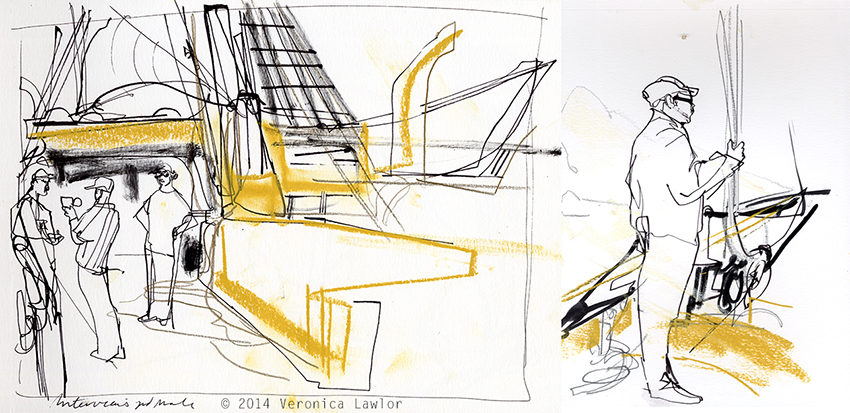

The crew was already hard at work, preparing to haul the anchor and get ready to move. They must have been awake at 4 am – they let the landlubbers sleep in, apparently. Crew members were running all over the deck, and Sam, the chief mate, was shouting out orders that were shouted back in repetition by the deckhands. I quickly began drawing the action, coffee can wait!

The pinkish morning light was struggling to take over the white sky as the soft rain barely fell on us. The atmosphere was beautiful and the weather felt very appropriate for our endeavor. The captain began organizing the other 38th voyagers to help bring up anchor. I stayed put on deck near the try pots and drew the scene. The 38th Voyagers were quite excited to be involved in the experience, and several of them looked with unconcealed elation at the stain of tar left on their hands by the rope.

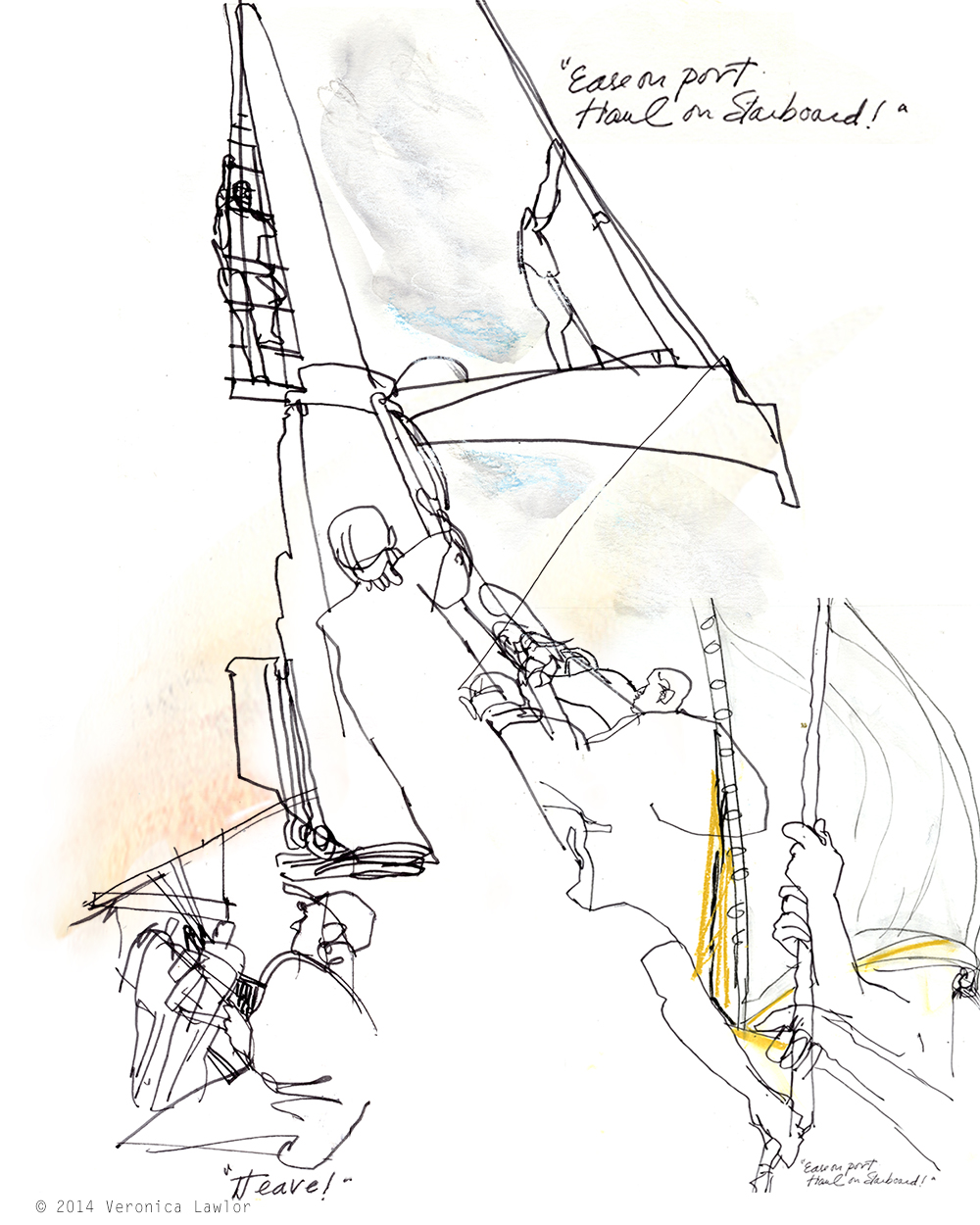

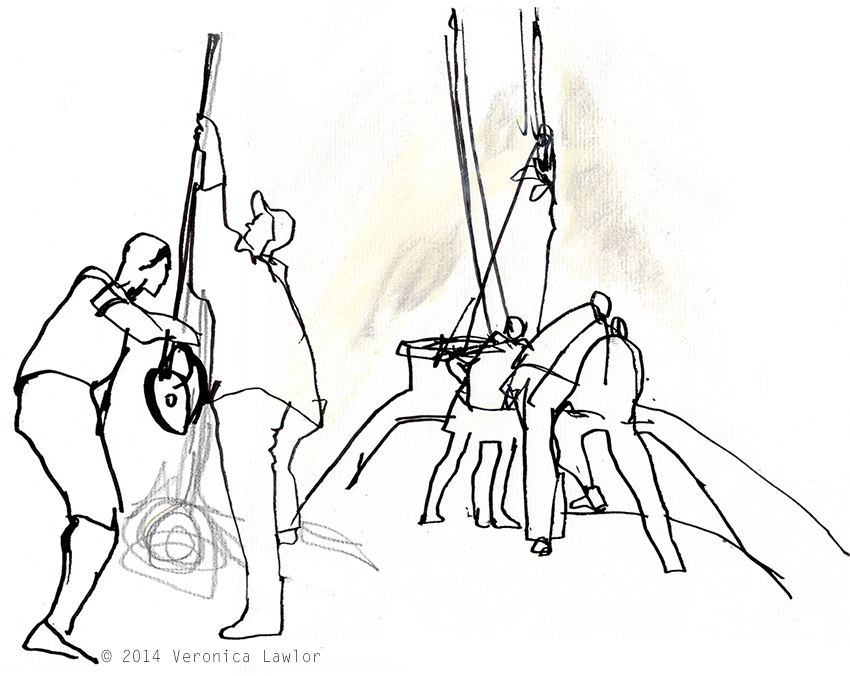

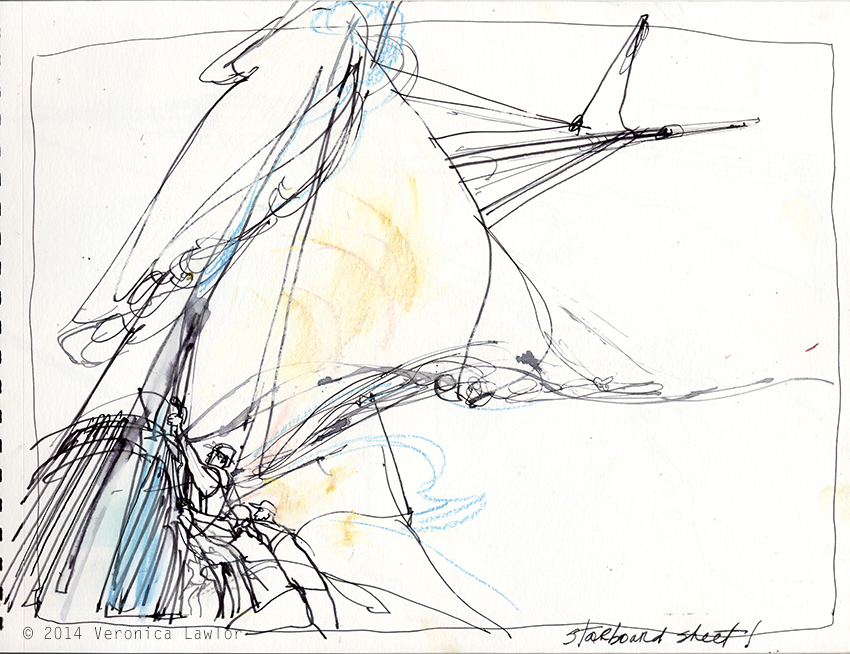

As a big storm was headed in our direction, the decision had been made for the tug Sirius to tow us most of the way to Boston, assisted by the sails. The crew slid the large cotton sails along the lines of rigging on rings, somewhat like a shower curtain, (although maybe the rain affected my perception of that.) The morning light hitting the sail creating a luminous glow, the rain fell gently, and the air was calm. We were going out to sea.

As a big storm was headed in our direction, the decision had been made for the tug Sirius to tow us most of the way to Boston, assisted by the sails. The crew slid the large cotton sails along the lines of rigging on rings, somewhat like a shower curtain, (although maybe the rain affected my perception of that.) The morning light hitting the sail creating a luminous glow, the rain fell gently, and the air was calm. We were going out to sea.

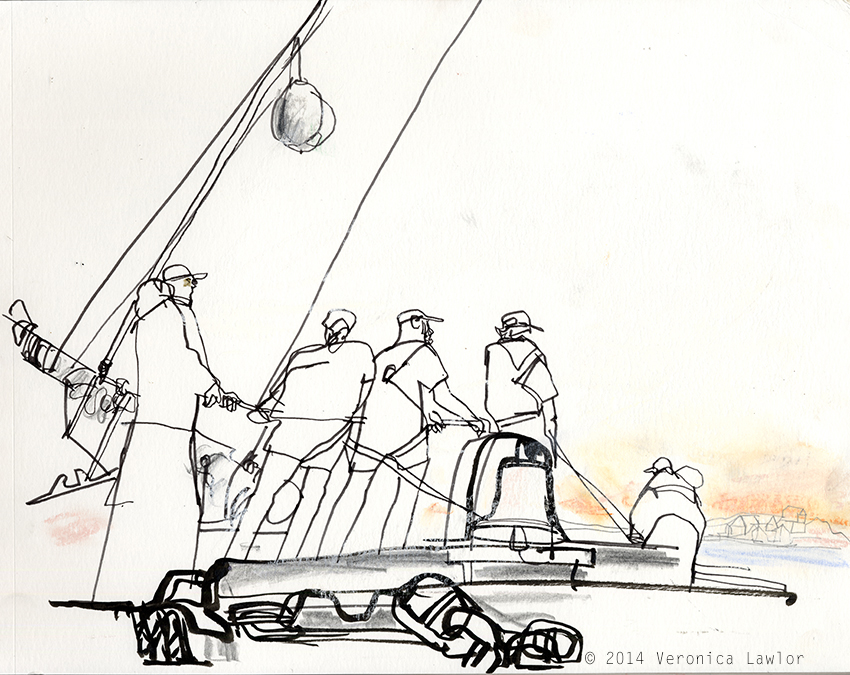

I went to the stern of the ship, where Dana was helping un-moor the tug Sirius, so the little boat could maneuver ahead and begin the towing. Sunrise was in full effect and Provincetown slept peacefully while the work to unfurl the sails continued at a frantic pace.

It may be cliché, but I can’t help but remark that a sailing vessel is the perfect metaphor for co-operation. I ran all over the deck that morning, trying to draw and keep up with the sailors as they heaved, pulled, pushed, climbed, unfurled, straightened out, bent, and maneuvered those cotton sails to their will.

The earliest illustration of a ship under sail can be found on a disc from Kuwait, dating from the late 5th millenium BC. The utter hubris of the thought that we could control the winds and the sea with a few wooden sticks and a piece of cloth is mind boggling, especially when I think of what technologies were not available in those early times. To my untrained sailing eyes, the whole set up feels precarious – “we’re going where, to do what, in what?” – would be my first thought upon joining a whaling voyage. It’s all about rope and sticks, and it amazes me every time I think about how the world changed due to the invention of sailing vessels, and the belief of sailors who trusted the ships with their lives.

The sails unfurled and billowed over the deck as the crew pulled the rigging this way and that. Like trying to control the breath of the universe and bending it to your will. I guess that’s why they call it “bending the sails.” If we could all pull together as a species to heal our environment in the way that this crew pulls together to get the sails up on the Morgan, I think there might just be a chance of leaving something worth having to the next generation.

As I was drawing, Robert and I spoke a little about the poetry of the winds filling the sails, and he mentioned Buddhist breath meditation: the philosophy that simple mindfulness of breath in meditation can lead to enlightenment, and knowing. Watching the white sails unfurling against a whiter sky, I felt certain that this must be true.

But for the crew, hard work was the meditation of the moment. They moved and breathed as one unit, and got the sails into the correct placement to aid little Sirius in our journey to Boston. The complications of the physics of sailing are myriad, and I am not an engineer, so for those readers interested to read more you can click this LINK as a beginning, or read a very clear “how to sail” article HERE.

But for the crew, hard work was the meditation of the moment. They moved and breathed as one unit, and got the sails into the correct placement to aid little Sirius in our journey to Boston. The complications of the physics of sailing are myriad, and I am not an engineer, so for those readers interested to read more you can click this LINK as a beginning, or read a very clear “how to sail” article HERE.

Once the sails were set and the Sirius attached, we began to move. My growling stomach and approaching headache prompted me to go to the stern of the ship, where there was a decidedly modern coffee machine. (Pragmatism wins again!)

As I reached for the coffee, a teasing voice called out, “it’s all gone!”

As I reached for the coffee, a teasing voice called out, “it’s all gone!”

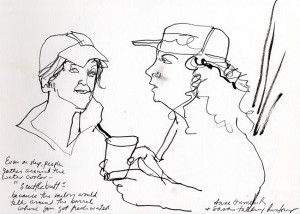

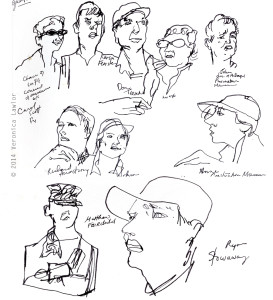

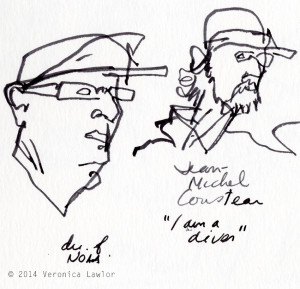

It was Jean-Michele Cousteau, the famous scientist, film maker, and son of Jacques Cousteau. I was happy that Jean-Michele was on our voyage, I admired his work and had met him two days earlier in Provincetown, where he had been complimentary toward the mural that Dalvero Academy was doing on the wharf. He had offered some good advice too – keep it simple in your explanation, let the art do the talking. Sweet.

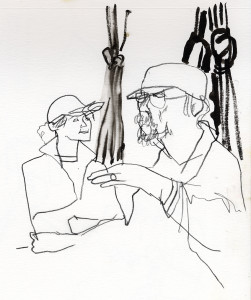

I respect his work, and loved his playfulness on deck. It seems that the most professional people know how to play the best. Definitely a flirt, he moved about teasing the female deck hands, who enjoyed flirting back. In this picture (up and to the left) he is having a more serious conversation with Anne Grimes Rand, president of the USS Constitution museum. And by the way, there was coffee to be had, thankfully. ;)

I sipped my coffee and noticed how even on a ship, everyone congregates around the water cooler, so to speak. Susan Funk told me that this is where we get the term, “scuttlebutt” since the sailors would gather around the barrel with fresh water, a butt (cask) that had been scuttled, meaning a hole put in it for water to get out. So much of our culture stems from the sea, I had no idea.

As everyone talked, I climbed below to have some breakfast: cereal, rolls, fruit. John and I perched on some barrels and talked a bit about the experience so far while we ate. Then we heard a call for everyone to gather on deck.

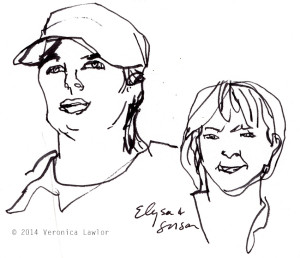

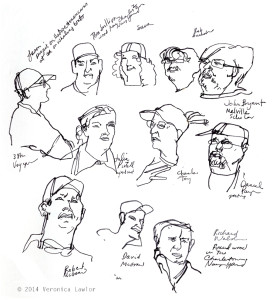

Captain Kip Files introduced himself and the rest of the Morgan crew and Mystic staff. He spoke about how thrilled he felt to be the captain of this vessel on this voyage, and the other Mystic people echoed his sentiment. Elysa Engelman, the Mystic museum director, told us that this was the voyage she chose, and how excited she was to be on the Morgan as we arrived in Boston harbor. Museum vice-president Susan Funk nodded in agreement, smiling.

Captain Kip Files introduced himself and the rest of the Morgan crew and Mystic staff. He spoke about how thrilled he felt to be the captain of this vessel on this voyage, and the other Mystic people echoed his sentiment. Elysa Engelman, the Mystic museum director, told us that this was the voyage she chose, and how excited she was to be on the Morgan as we arrived in Boston harbor. Museum vice-president Susan Funk nodded in agreement, smiling.

We were all asked to introduce ourselves – 38th Voyagers, guests, and patrons – and say a few words about how we arrived on the Morgan, and why we wanted to be there. Some of us had more to say than others, but we all told a similar tale of how we wanted to be a part of this historic event, and how Mystic Seaport was unprecedented to create this experience for us. The former president of Mystic, Douglas Teeson, spoke of the beginnings of the restoration, and how he never imagined she would sail. He graciously thanked current president Stephen White.

And we spoke of how important it was to take the largest and only surviving symbol of our whaling past and environmental degradation, and turn it into the largest new symbol of our changing perceptions of the natural world, and our commitment to heal it. Ryan, the stowaway, added that he felt honored to be the first person to see whales from aloft in 100 years, especially since there was no hunt to follow!

We all had many things to say.

But Jean-Michele said the most: “I am Jean-Michele. I am a diver.” We laughed, but it was quite profound. Simple humility in the face of nature, a good lesson for all of us.

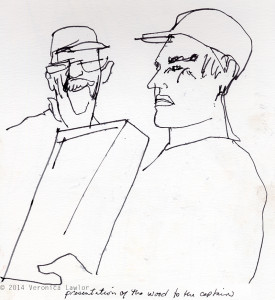

And then Thomas Sullivan made a formal presentation to the Captain of the wood from the Charlestown Navy Yard, that his family had salvaged and donated to Mystic Seaport for the restoration of the Morgan. (Read more HERE.) Thomas has been taking this wood around the world, including sailing around the Cape of Good Hope, and the voyage on board the Morgan was an important part of the trip. The captain gamely thanked Thomas, and photos were taken.

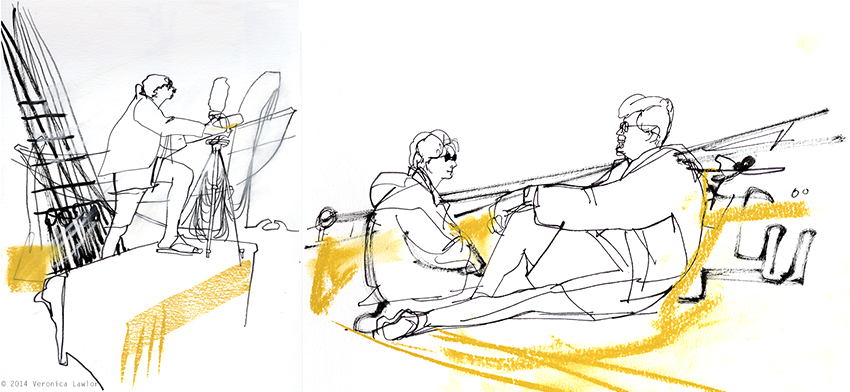

The rain had let up, and people were moving about the deck, settling in as we moved smoothly through the waters of Cape Cod Bay. Robert set up his navigation equipment, there was a videographer interviewing the Second Mate, and people sat in groups, discussing matters great and small.

Robert with his equipment, John and Carol converse.

Only the crew did not relax, and Sam, the First Mate, was ever vigilant at the prow.

Paul O-Pecko watches as Sean is interviewed, Sam looks out.

I asked Sam about the 38th voyage, and what he thought he would take away from it. “About 2/3rd of the hull,” he answered, laughing, “we’re gonna cut her off right at the foreshrouds.”

“No, seriously,” he continued, “I’ve taken away a really great experience to sail the real deal, and to have been able to get to know the ship, just a little bit, ’cause she’s such a sweetheart of a sailor. And you can tell why there were people for 90 years who thought it was worth it to take this ship to sea.” I asked him what he meant by that: “She does everything you want her to do, and there’s no mystery to it. You throw her up into the wind, and she does that the way you want her to, she heaves to, she stops the way you want her to…she’s very docile. And that’s something actually something that often, in replica square riggers, they don’t do things that you want them to do, or they will end up doing things that surprise you…the surprising thing about this one is it does everything that we think it should do. From all the accounts that you read of how they used to sail these ships…you sail this one and this one actually does do it. You say, oh, that’s ’cause it’s the genuine article.”

He looked out over the water and continued: “You can’t build this ship again, the way this ship is… you can’t actually replicate this…there’s stability requirements for modern construction, things that alter the shape, and the intent, and the spirit of what these ships were, just enough that you have these sort of unintended consequences that you almost can’t really measure in the sailing qualities, but you just know that they’re not there.”

“It’s like the difference that makes the difference,” I said, quoting Gregory Bateson.

“Right,” he replied, “…and this whole ship, it’s a painting, it’s this piece of artwork with all these details, that if you take one shade of purple out of the painting it looks a little different, but you’re not really sure why.”

Beautifully said.

I wanted to ask him more, but he very quickly had to get back to work. More yelling, pulling, heaving, calling out, and such, as the deck became alive again with the movements of the sailors. The weather had shifted, and the sails had to shift with it.

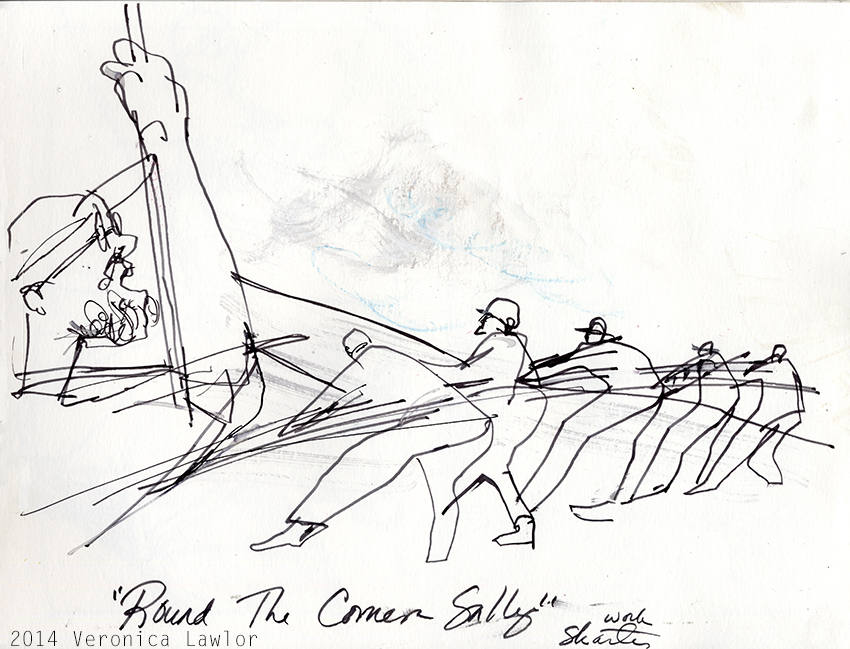

“Round the Corner Sally!”

The call out and repeat of a traditional work shanty rang out across the deck. The shanty singing kept spirits high and muscles strong as the sailors pulled the line to get the sails where they needed to be. You could just see the adrenaline pumping; it was thrilling to watch.

And the crew was in the rigging, and the sails shifted again…

Captain Kip Files and Chief Mate Sam Sikkema look out into the fog.

Captain Kip Files and Chief Mate Sam Sikkema look out into the fog.

So soulfully written and beautifully sketched Miss Veronica.

Lively sketches, and great musings and reportage Veronica!

This journey is so fascinating as lived through your words and sketches. The penultimate drawing is my favourite from part 2 but in all of them I envy how you capture the energy and action in so few lines.

Thank you everyone, for your comments. It was hard to keep up with the crew while I drew these, but a wonderful challenge!

What amazing detailed sketches you were able to create….my husband is an open swim masters, and he knows of woman, here in Richmond, VA who will be swimming this same bay soon….19+ miles from Plymouth to Provincetown. The sailors are such an incredible team, as will be her support crew to assist her with her journey. Here’s to hoping the Great White Shark sited off of Duxbury Town Beach has decided to swim in the deep Atlantic for the remainder of 2014. I shall meet you in Sketchbook Skool, Klass 3 this October.

Hi Holly, thanks for your comments. That swim sounds amazing – wonder if she’ll see any humpback whales along the way?

Looking forward to Klass 3 – see you there!